Musical Soundalike of the Day, 4/29/2024

Something I’m trying since I’ve been having trouble keeping up in this blog, first a piece of music that sounds like a cross between previously-written pieces.

+

=

Let me know if the videos don’t work.

Something I’m trying since I’ve been having trouble keeping up in this blog, first a piece of music that sounds like a cross between previously-written pieces.

Let me know if the videos don’t work.

Did some more class grinding in Traveller’s Tablet worlds before returning to the past Nottagen to finish the final quest. Maribel has left my party, replaced by Aishe, whom I made a Warrior since she has some ranks for that class. The Hero is a Priest, Ruff an Armamentalist, and Sir Mervyn a Sage. Maribel was a Jester before she left.

Beat this baby. Expect a review eventually.

Got the Mysterious Fragment from the present-day Sullk Tower, and gave one of the monster-obtained Traveller’s Tablets dungeons a shot. Despite the enemies in one being super-weak, battles with them still count towards vocation advancement. The Hero is still a Gladiator, Maribel finallymastered Mage and is now a Sage, while Ruff is still a Drake slime and Sir Mervyn a Malevolantern. Doing the second part of Nottagen’s past right now.

I’m at the start of Gaia, with Feena back in my party. The end is near…

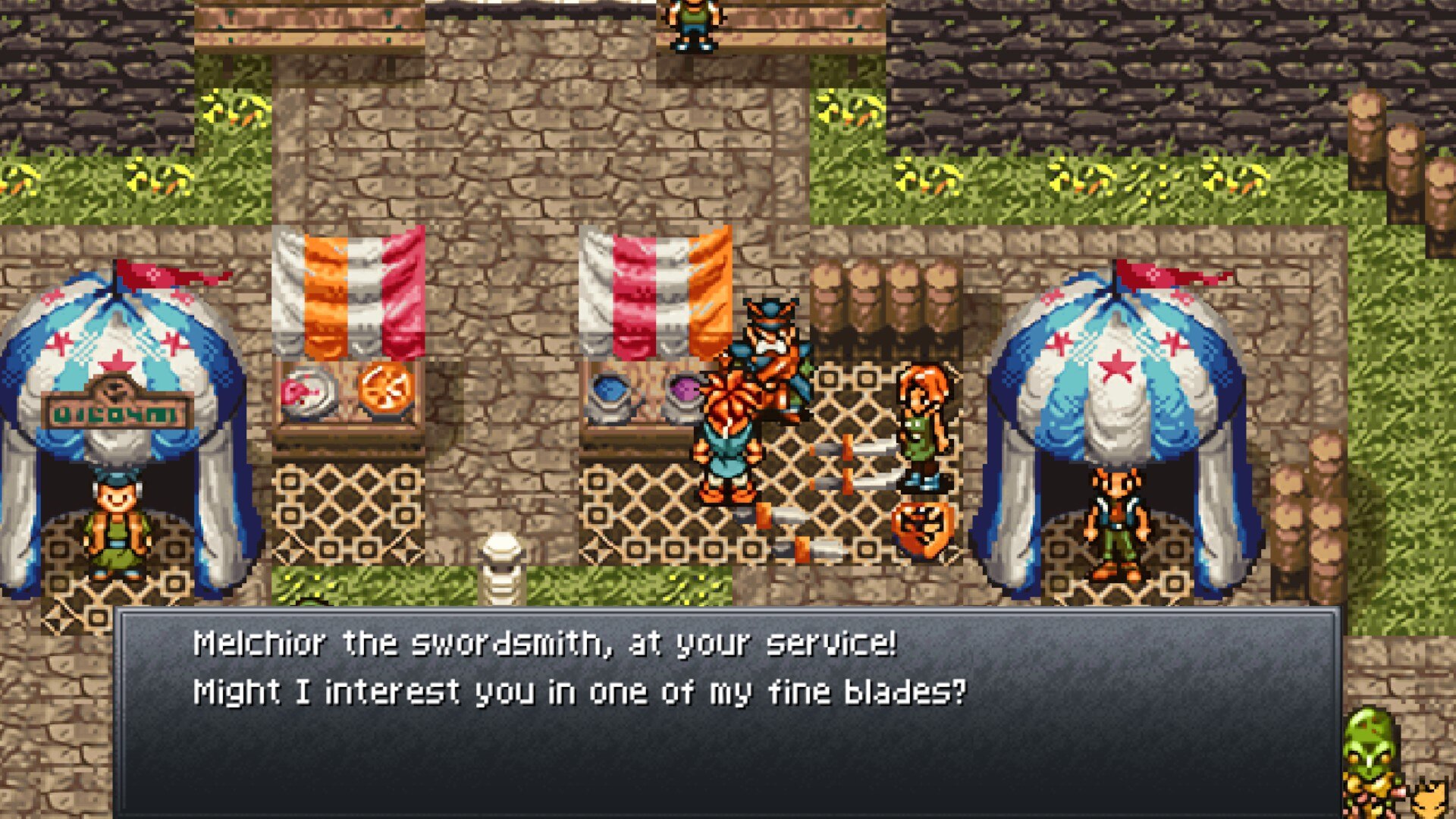

Before Square and Enix merged, Final Fantasy creator Hironobu Sakaguchi, along with Yuji Horii and Akira Toriyama, the respective architect and character designer of the Dragon Quest series, banded to develop an RPG under the former company’s banner heavily utilizing content excised from the planned debut of Secret of Mana on the Super NES’s aborted CD add-on when Nintendo sought partnership with Sony when their negotiations fell through. The final product was titled Chrono Trigger, seeing original release on the Big N’s 16-bit console and future ports to platforms that include the PlayStation, Nintendo DS, iOS, and most recently, Steam. Does it still hold up today?

The game opens in 1000 AD when the protagonist Crono’s mother awakens him on the day the Millennial Fair, which celebrates the founding of the kingdom Guardia, begins. At the festival, he bumps into a mysterious maiden named Marle, whom he takes to test his friend Lucca’s teleportation device, which strangely resonates with her pendant and mistakenly sends her four centuries into the past. Thus, Crono gives chase, discovering various temporal events and conspiracies culminating in the destruction of the world in 1999 AD by an entity called Lavos and recruiting others to secure the timeline.

Even in the original’s time, Chrono Trigger was not the first Japanese RPG to emphasize time travel, with that honor going to SaGa 3, which received the phony moniker Final Fantasy Legend III from Square’s North American branch when it was translated years before. However, the game weaves its story effectively, with the characters being endearing and often having intricate backstories, the various substories being interesting, events in historical periods impacting the future, a few plot differences dependent upon the player’s party composition, and different endings that depend upon actions taken throughout the quest.

However, many negative plot beats abound. Among them are Guardia’s soldiers leaving Crono with his weapon and armor on when incarcerated early in the narrative, the tale of a “legendary hero,” and elements derived from literature like the repair of a broken ancestral blade, a plot point from The Lord of the Rings. Other unoriginal elements include a dystopian future and an evil queen; other tropes from previous RPGs, like a character having to relearn all powers from scratch when joining your party and a doomed floating continent also appear. Additional “why” moments like cavemen in hiding emerging to glimpse an approaching tidal wave before returning to safety are also present. Fortunately, these don’t heavily dent an otherwise enjoyable plot.

The original translation by Ted Woolsey was one of the better ones in its era, receiving much of the polish it had when ported to the Nintendo DS. As is expected of any RPG released today, the dialogue is legible, and very few spelling and grammar errors exist. Most Japanese-to-English name changes were also for the better, like the names of the Gurus of Zeal, renamed after the Magi that visited the infant Jesus after his birth, with their original names being far more comical. Magus’ generals, furthermore, had the names of condiments in the Japanese dialogue, although Woolsey changed their names to Ozzie, Slash, and Flea after musicians well known to Anglophone gamers.

While Chrono Trigger features an overworld, it relegates enemy encounters to dungeons, with foes visible to fight in most of them. Contacting enemies or coming near them triggers combat, but many cases come where they’re hidden and emerge to engage Crono and his party. Battles bequeath the active time system of the Final Fantasy franchise, with the three frontline characters having gauges that, when filled, allow them to perform commands. As in Hironobu Sakaguchi’s flagship Square franchise, players can choose between active mode, where the battle action continues while they peruse Tech and item menus, or wait mode, where the action stops during navigation of said inventories.

However, the wait mode doesn’t work universally, for example, not while targeting monsters to attack or execute Techs against or anytime outside the Tech and item menus, even when all three characters’ active time gauges fill, which would have been welcome. Attacking using equipped weapons, using MP-consuming Techs, and consuming items are the primary battle commands, but a typical RPG staple, defending to reduce damage, is oddly absent. Players can escape by holding the L and R buttons on whatever input device they use, which usually works except during mandatory battles or standard boss fights.

Winning battles nets all participating characters experience for occasional leveling, money, TP to unlock more powerful Techs, and maybe an item or two. Depending upon the player’s party composition, characters can learn Double and Triple Techs that allow combination skills targeting all allies, one enemy, or all enemies, which can help hasten even the most daunting battles. Many bosses require a specific strategy to defeat them, whether exploiting an elemental weakness or offing boss units in the correct order (critical to the absolute final battle, hint, hint). Other issues aside from those mentioned include the existence of Techs whose range depends on a character’s current location but the lack of any means to move them across the battlefield. Regardless, the game mechanics form a satisfying whole.

In contrast, control is a mixed bag. However, the Steam port has numerous quality-of-life additions, like autosaving, a suspend save, and autodashing. Other positive usability features from previous versions remain, including diagonal character movement, an in-game clock the player can view at any time and not just while saving (which oddly seems endemic to many contemporary Japanese RPGs for some reason), the ability to walk around while minor NPCs are talking, sortable item inventory categories, being able to see how weapons and armor increase or decrease stats before purchasing them, item and magic descriptions, and overall polished menus.

However, those in charge of the Steam port could have addressed issues that include a potential glitch when booting the game that can prevent it from even going to the title screen, the absence of an auto-equip feature for the player’s party, the lack of dungeon maps, no pausing outside of battle, no fast travel in the early portion of the game, the inability to speed up increasing item quantity when purchasing consumables from shops, the pause feature in combat not muting the volume (and heaven knows I hate having to fiddle with my television remote), many secrets being tedious to discover without the internet, and a late-game missable sidequest dependent upon interacting with a minor NPC earlier in the storyline. Even so, the controls aren’t absolute dealbreakers when pondering a purchase.

Chrono Trigger marked the musical debut of composer Yasunori Mitsuda, who, with help from resident Square composer Nobuo Uematsu, provided an endearing soundtrack. The titular main musical piece has several remixes throughout the game, with each character also having a musical motif, including Marle’s lullaby, Lucca’s triumphant anthem, Frog’s whistle-along refrain (which somewhat resembles “When Johnny Comes Marching Home”), and Robo’s techno tune, whose resemblance to Rick Astley’s “Never Gonna Give You Up,” as Mitsuda noted when informed of it, was coincidental.

Other notable tracks include the Fiendlord’s battle theme, which has an orchestral flamenco feel (as does that during the penultimate final boss fight), and “Corridors of Time,” the theme for the floating continent during the Ice Age, which utilizes digitized Indian instrumentation. The minor jingles have pleasant melodies, like the sleeping theme, with the sound team adding quirks like Frog’s croaking and Robo’s beeping and buzzing. However, the musical variety, especially regarding the standard battle theme, can often be minimal, many areas lack unique themes, and a few “why” tracks like Gato’s jingle and the prehistoric “Burn! Bobonga!” abound. Regardless, the aural aspect is a boon to the game.

Its original version having been of the final Japanese RPGs released on the Super NES, Chrono Trigger featured polished visuals with vibrant colors, beautiful environments, character sprites having reasonable proportions and emotional spectra, fluid animation by the player’s party and enemies, stunning battle effects, and the anime cutscenes introduced in the PlayStation port and onward, mostly readjusted for contemporary television screens. Akira Toriyama provided the character and monster designs, most being well-designed, even if most human characters have similar faces typical of the artist’s work, alongside many reskins among the latter.

Other graphical issues include countless recycled nonplayer character sprites, a few that have odd appearances such as those for the old green-haired women, hints of pixilation even with upscaling and smoothing enabled, character sprites not facing diagonally, many NPCs absurdly walking in place, and Mode 7 graininess especially evident during the ending credits. The porting team further left maybe a few anime cutscenes from the PlayStation and Nintendo DS ports out (but mercifully, the one appearing after the ending credits, which adds to the game’s story and slightly connects to sequel Chrono Cross, remains). Otherwise, the graphics serve the game well.

Finally, playtime will vary, depending upon the player’s skill, with 24 hours being an average time for an initial playthrough, even with most sidequests partaken in. Chrono Trigger was the first RPG to term and popularize the New Game Plus, even if a handful of Japanese games before featured similar modes. Combined with significant extra content, like potential plot differences, around a dozen different endings, and discovering every secret, the time-travel RPG is the epitome of replayability.

Overall, Chrono Trigger, pun intended, does indeed stand the test of time, given its enjoyable aspects that include its solid game mechanics enhanced by contemporary features such as a turbo mode, the intricate narrative with potential variations and around a dozen different endings, the beautiful soundtrack, and the upscaled visuals. However, while inarguably a classic, “masterpiece” is an overstatement since there are numerous issues bequeathed from prior releases, like the slight inaccessibility to those experiencing it for the first time, given the difficulty of discovering helpful elements without referencing the internet and coasting through the game in general.

Furthermore, while contemporary quality-of-life features such as auto-saving and a suspend save exist, the game could have used more polish in the usability department. The localization quality is also inconsistent, musical variety can be lacking, and some aspects of the visuals haven’t aged well, even with the upscaling and smoothing. Regardless, it was in many respects a turning point for Japanese RPGs after its original release, especially with the significant lasting appeal that its various endings and New Game Plus feature contributed to the realm of roleplaying games, and, while imperfect, is easily a bucket-list title necessitating at least one playthrough from those with a passing interest in Eastern video gaming.

This review is based on a single playthrough of a digital Steam copy purchased and downloaded to the reviewer’s Steam Deck, played on a television through the Docking Station.

| Score Breakdown | |

|---|---|

| The Good | The Bad |

| Great gameplay with new features like turbo mode. Excellent story with variations on plot and different endings. Enjoyable soundtrack. Good graphics with choice of higher resolution. Plenty lasting appeal. | Can be difficult to cheese through in initial playthrough. Some usability issues. Inconsistent translation quality. Musical variety can be lacking at points. Some aspects of the visuals haven’t aged well. |

| The Bottom Line | |

| Not perfect, but definitely a bucket list JRPG. | |

| Platform | Steam |

| Game Mechanics | 9.0/10 |

| Control | 6.0/10 |

| Story | 9.0/10 |

| Localization | 6.5/10 |

| Aurals | 8.5/10 |

| Visuals | 7.5/10 |

| Lasting Appeal | 9.5/10 |

| Difficulty | Moderate |

| Playtime | 24+ Hours |

| Overall: 8.0/10 | |

Back when my brothers and I were obsessed with the works of Blizzard Entertainment, we discovered the first of their Diablo series, with whose sequel and expansion I would spend significant time, given the multitude of classes. The third Diablo game wouldn’t see release until a decade after the second, and the fourth game, Diablo IV, would have a similar wait before it came out. The fourth entry, as a few other video game series in Japan and the West have, leaps into an open-world setting, like Nintendo’s Zelda and Pokémon franchises. Does it do so well?

The fourth game occurs half a century after the third in Sanctuary, where cultists summon the new antagonist, Lilith, daughter of the demon Mephisto, who seeks to fill the power vacuum created by the decline of angels and demons across the land. The narrative has varying cutscenes depending on which character class the player selects, along with plenty of texts that reveal backstories, sidequest subplots, and a well-developed central plot. A few narrative gaps still exist between the third and fourth games; however, the story remains engaging throughout the experience.

Players can select from five classes: Barbarian, Sorcerer, Druid, Rogue, and Necromancer, each with their unique ability trees, and choose a difficulty, accommodating to gamers of divergent skill levels. Regardless of whomever the player selects, all have a health orb whose depletion means death (in which case they can resurrect at the expense of a tenth of their equipment’s durability), a fixed number of potions with which they can recover their health (with upgrades to this amount found sporadically through Sanctuary’s dungeons), Spirit that the use of many abilities consumes (and which standard attacks can gradually recover), and many skills with a cooldown time before they can use them again.

Killing enemies earns the player experience, with foes frequently dropping money and treasure. Before reaching fifty levels, leveling gives players a point they can put into their class’s respective tree to unlock various abilities and bonuses. If players wish to do so, they can pay to reset points and redistribute them however they please. Players stop earning skill points when their character reaches the mentioned threshold. At that time, their Paragon Board unlocks, with its points acquired at fixed times while advancing to the next level and allowing for increased stats.

In towns, the player can repair their equipment (which doesn’t seem to wear down regardless of whatever combat they’ve seen, except upon death), replenish their potions and health, purchase new gear, and so forth, like in prior games. The mechanics work well, with plenty of quick action and rewarding exploration; however, players can’t pause the game, and the potential to waste a lot of time against bosses exists (though depleting their health to fixed amounts will cause them to drop health potions). Regardless, the fourth game nicely fuses elements from the second and third entries.

Control, however, could have used improvement. Among the primary issues is that one needs a constant internet connection and a PlayStation Plus membership to play Diablo IV in the first place, which is ridiculous since I had spent $60+ for my physical copy. Even so, there are a few quality-of-life features such as subtitles for the voiced dialogue, adjustable text size, helpful in-game maps with objective markers, the ability to skip cutscenes and through some dialogue (though the latter feature isn’t available during “cinematic” scenes), the option to exit dungeons instantly after completing them (though some exceptions exist), and readily-available teleportation across Sanctuary, even when the player is far away from a teleport point. As mentioned, however, the game is unpausable, along with other issues like the absence of an in-game measure of total playtime, the vagueness of a few sidequest objectives, and how the game doesn’t preserve the player’s current location whenever they quit the game and restart later. Ultimately, the fourth game could have interfaced better with players.

While the soundtrack features good instrumentation and has some callbacks to prior Diablo games, the fourth installment’s music is otherwise unremarkable, given the lack of memorable tracks and overreliance upon ambiance, which seems typical of most Western video games. However, the voice acting and sound effects shine brighter.

Diablo IV executes its visuals nicely, with realistic art direction for the human and nonhuman characters and players able to customize their protagonist’s appearance. Different equipment also affects character looks, with the environments and colors being believable, the weather and illumination effects gorgeous, and the critical story scenes having an engaging cinematic style. However, the typical imperfections of three-dimensional visuals abound, like poor collision detection, blurry and pixilated texturing, and occasional choppiness.

Given the lack of an in-game clock, assessment of total playtime is difficult. However, I sometimes used my watch timer and estimated I finished the game in over seventy-two hours, consisting of significant time exploring Sanctuary and completing sidequests, although advancing the main quest doesn’t take long. Replayability exists with the vastness of the game world, which I hadn’t fully mapped, countless sidequests, achievements, and so forth. However, the need for a PlayStation Plus membership to continue playing, which I immediately canceled upon finishing the main quest, will deter many from devoting additional time to the game.

Ultimately, Diablo IV was an ambitious production from Blizzard and nicely accomplishes its transition of the series to open-world format, in my opinion, even better than other major video game franchises that have done the same despite their “universally positive” reception. The gameplay is fun and rewarding, the narrative is intricate regarding its backstory and “present” plotline, the visuals are top-notch, and plenty of extra content can occupy players endlessly. However, issues such as the need for a constant internet connection and PlayStation Plus membership to play, various interface problems, and unremarkable sound prevent it from “game of the year” status. Despite its faults, it warrants a playthrough from those who enjoyed its predecessors and is one of 2023’s better releases.

This review is based on a playthrough of a physical copy purchased by the reviewer as a Druid.

| Score Breakdown | |

|---|---|

| The Good | The Bad |

| Variety of classes to choose from. Lots to explore in Sanctuary. Well-developed narrative. Nice graphics. Plenty of lasting appeal. | Requires constant internet connection and PlayStation Plus membership. Quitting the game doesn’t always preserve quest progress. Lackluster soundtrack. |

| The Bottom Line | |

| One of the stronger major releases of 2023. | |

| Platform | PlayStation 4 |

| Game Mechanics | 9.0/10 |

| Control | 6.0/10 |

| Story | 9.5/10 |

| Aurals | 7.0/10 |

| Visuals | 8.0/10 |

| Lasting Appeal | 8.5/10 |

| Difficulty | Adjustable |

| Playtime | 72+ Hours |

| Overall: 8.0/10 | |

When Nintendo’s latest portable system was the Nintendo DS, Square-Enix announced a remake of the Zenithian trilogy of the Dragon Quest series, comprising the fourth through sixth installments, with North American release announced for all three, as the franchise had somewhat been experiencing a golden age outside Japan with the success of Journey of the Cursed King. However, unlike Cursed King, the rereleases of the fourth and fifth games, because of invisible advertising, didn’t sell as well, leaving the fate of the sixth and final Zenithian Dragon Quest in the air. Eventually, Nintendo took charge of localization and reannounced the trilogy’s conclusion as Dragon Quest VI: Realms of Revelation, but it kept its original English subtitle, The Realms of Reverie, in Europe. The title saw a port to iOS devices, with an experience on par with the rest of the series.

Combat is turn-based and randomly encountered, with the sixth installment following the tried turn-based tradition of the player inputting various commands for their characters and letting them and the enemy beat up one another in a round. Turn order can be inconsistent as in other entries, and the escape option doesn’t always work, with a few instances of accidentally tapping it when guaranteed not to work, like against bosses. While exploring the overworld, the player can swap party members out from their carriage, an option sometimes available in some dungeons when the player’s carriage comes along. As in prior Zenithian Dragon Quests, AI options are available for all characters except the protagonist, which can work well depending on the situation. Victory nets all living participants, including those not in the party, experience to level occasionally, money, and maybe an item. Death results in the player being transported to the last church with only the hero alive and his allies dead, with early-game revival expenses potentially burdensome.

Eventually, the player accesses the job system, each with their strengths and weaknesses, with a certain number of battles with enemies on par with the player’s levels or any in the Dark World necessary to advance, acquire new skills that become permanent parts of a character’s skill set regardless of occupation, and ultimately master skills, with higher-level careers available depending upon base classes mastered. Despite many powerful free skills, the game is no cakewalk, especially the main final boss. There is some early-game hell as well, like the initial revival spell failing half the time, and things such as skills on the part of the player and enemy affect all one at a time, which can drag out fights where the player has their carriage present. The game mechanics have many positives, but the archaic elements from previous series entries can spoil things.

As usual, moreover, interaction leaves room for improvement. The menus are superficially clean, but shopping for equipment and items is troublesome, given the countless confirmations, alongside the taxing nature of saving the game, the unavailability of the quicksave in dungeons, and a general poor direction on how to advance the main storyline or where to go next. Dungeons don’t have maps, either; a map for the underwater version of the lower world would have also been welcome, given its numerous points of interest. Hopefully, one day, the franchise will abandon these archaic traditions.

The story is enjoyable for a Dragon Quest game, focusing on two parallel worlds and a conflict between the playable characters and a villain named Murdaw. All characters have a story behind them, and the various subplots are detailed. However, the game is frequently unclear on how to advance the central storyline. Some plot beats, as well, are derivative, such as amnesia and a higher power behind everything. The localization is top-notch, with a hurricane of puns characteristic of contemporary translations of the series, with maybe some minor odd lines such as the ever-present “But the enemies are too stunned to move!” Even so, the narrative is a significant driving factor.

Composer Koichi Sugiyama, as usual, does a superb job with the soundtrack, with every track being enjoyable. However, some silence abounds, and the battle sounds are still dated.

The sixth entry utilizes the same graphical style as its Nintendo DS predecessors. The sprites and scenery look nice, despite pixilation, and fluidly animated enemies designed by Akira Toriyama dazzle in battle. However, many foes are reskinned, and the perspective of combat remains in first-person, like classic series entries. Camera rotation during exploration isn’t always available, which would have been handy given a plot quest where the player must tail a non-player character without being caught. The visuals aren’t an eyesore but show their age.

Finally, playtime ranges from twenty-four to forty-eight hours, depending upon how much grinding of levels and classes the player needs to make it through the game. Some lasting appeal exists in mastering all character classes, not to mention a post-game dungeon. However, there are no plot variations or achievements, and most players will likely want to move to other games.

In summation, Dragon Quest VI hits many positive notes, particularly with its solid class system, enjoyable narrative with polished translation, and superb soundtrack. However, many aspects leave room for improvement, including the occasional difficulty of spikes throughout the main quest, the retention of the franchise’s archaic traditions that affect combat and control adversely, the frequent poor direction on how to advance the main storyline, the questionable quicksave feature, and the dated visuals. Those who have enjoyed other games in the franchise will likely be able to look beyond its flaws. Furthermore, since the story doesn’t have much connection to other games in the series beyond its trilogy, those unversed in the franchise may find this port a decent romp.

This review is based on a playthrough to the standard ending with no postgame content attempted.

| Score Breakdown | |

|---|---|

| The Good | The Bad |

| Great class system. Enjoyable story and translation Excellent soundtrack. | Retains franchise’s archaic elements. Poor direction on where to go next. Graphics show their age. |

| The Bottom Line | |

| Typical Dragon Quest. | |

| Platform | iOS |

| Game Mechanics | 5.5/10 |

| Control | 5.0/10 |

| Story | 9.0/10 |

| Localization | 9.5/10 |

| Aurals | 9.5/10 |

| Visuals | 6.5/10 |

| Lasting Appeal | 5.0/10 |

| Difficulty | Moderate to Hard |

| Playtime | 24-48 Hours |

| Overall: 7.0/10 | |

The Etrian Odyssey series would attract attention from the gaming community due to its throwback to old-school first-person dungeon crawlers like Wizardry, lasting until the Nintendo 3DS became a defunct system. However, in 2023, the company released remasters of the first three games in the franchise for the Nintendo Switch and Steam, a fortunate thing for those who missed out on them and wished not to pay the exorbitant prices that Atlus games tended to receive after physical versions of their games fell out of print. Etrian Odyssey III HD, like the original tertiary entry of the franchise before it, would shake things up a little in the gameplay department, the remaster making it more accessible to mainstream audiences.

The third entry occurs primarily in the ocean city of Armoroad, which once prospered greatly with a highly developed civilization that fell underwater with a great earthquake, with various adventurers, including the guild the player creates, seeking to unravel its mysteries. While the members of the customizable party lack a story behind them, the other aspects of the narrative are surprisingly well-developed, with plenty of substories, many in the sea exploration sidequest and a few within the Yggdrasil Labyrinth, alongside a significant plot decision that affects the endgame and warrants another playthrough. However, a few moments abound that leave the player clueless on how to further the central storyline unless they pay pedantic attention to the dialogue. Regardless, the plot is a benefit to the game overall.

The translation is also executed well, with a deficit of spelling and grammar errors, legible dialogue, and good naming conventions, aside from occasional awkward lines.

Etrian Odyssey III shares many mechanical similarities with its predecessors, with the player first needing to create a Guild of at least five characters of different classes to traverse the Yggdrasil Labyrinth. Encounters are still random yet anticipatable, with an indicator shifting from blue to red to denote their closeness. In battle, the player inputs commands for each character, which include attacking with their equipped weapon, defending to reduce damage, executing a TP-consuming skill, using a consumable item from the party inventory, executing a limit skill that requires the users to have their respective gauges to be at their maximums, or attempting to escape, the player having up to five chances to do so in case one or more fails.

Afterward, the characters and the enemy exchange commands depending upon agility, with some classes having skills that can affect turn order and thus negate the typical turn-based battle issue of healing coming to allies with low health too late. How the game handles death depends upon the difficulty setting, with the Picnic mode taking players back to town with nothing lost and higher settings resulting in a Game Over but a chance to preserve dungeon map progress. Victory nets all characters still alive experience for occasionally increased levels and parts from the defeated enemies, which the player can sell for money and unlock new items and equipment for sale in town.

Leveling nets characters a point they can invest into their skill tree to unlock new active and passive abilities. Upon reaching the Third Stratum, the player can select a subclass for their characters, which nets them bonus skill points and the opportunity to obtain the abilities of another class. Some class combinations can be incredibly ideal; for instance, I had an Arbalist with elemental attack abilities subclassed as a Zodiac, whose passive magical skill bonuses made for a killer mix. As in prior Etrians, powerful enemies called FOEs wander the Yggdrasil Labyrinth, with the recommendation to avoid them initially ringing true on difficulties above Picnic.

Etrian Odyssey III introduced a major sidequest that consists of sailing the seas around Armoroad, with the player needing to outfit a ship with food supplies that dictate how far they can travel alongside nautical equipment such as a sail that can allow players to traverse several tiles with one movement and a ram that can allow their vessel to bypass obstacles such as coral reefs. When the player reaches new landmarks, sidequests unlock where the player can send characters currently in their active party to battle powerful enemies alongside AI-controlled allies. Their experience rewards can provide an edge in the battles of the Yggdrasil Labyrinth.

Players can also obtain experience from story missions and the tavern quests, and while some of the latter and the sea exploration may necessitate the use of the internet, completing all is scarcely necessary to finish the main quest. Ultimately, I had a blast with the mechanics, with the adjustable difficulty accommodating players of different skill levels and putting the game above and beyond the original Nintendo DS version. A few class abilities can nullify the typical shortcomings of traditional turn-based battle systems, and the endless potential for subclassing combinations is another plus, making the high-definition port a pinnacle of classical-style RPG mechanics.

As with its precursors, Etrian Odyssey III HD features an intricate mapping system, with players able to set it so that tiles and walls in the Yggdrasil Labyrinth are automapped. While it’s up to players to place icons indicating elements like shortcuts and doors, the developers adapted the control surprisingly well for the remaster. A suspend save is also available to accommodate players with tight schedules outside gaming, and the base menu system is easy to handle. The only real issues are the inability to see how equipment increases or decreases character stats when pawning it and the weak in-game direction at many points on how to advance the central storyline.

As with other series entries, Yuzo Koshiro composed the soundtrack, which is just as riveting as in the Nintendo DS version. Plenty of catchy tracks of different styles abound, starting from the main Stratum themes and concluding with the ending credits music. There are a few silent portions, but the remaster is an absolute aural joy.

The remastered visuals are mostly a joy to behold as well, with excellent character and monster designs, great colors, pretty environments, and mostly smooth three-dimensional effects within the Yggdrasil Labyrinth and on the seas around Armoroad. Granted, some of the environmental textures are blurry and pixilated, and many enemy designs consist of reskins and are completely inanimate in combat. Even so, the game is far from an eyesore.

Finally, playtime can be on par with the third entry’s predecessors, somewhere from twelve to twenty-four hours, with lasting appeal existing in the form of Steam Achievements, postgame content, messing with different party setups, and so forth.

In conclusion, Etrian Odyssey III HD is the final feather in the cap of the Origins Collection, on par with its preceding remasters, given its intricate gameplay mechanics and mapping, tight control, well-developed storylines, and solid sight and sound. However, there are a few blemishes in the interaction, story, and visual departments, given the potential to become lost if not paying close attention to the dialogue, the lack of backstory for the player’s characters, and how the visuals retain much of the lazy design choices of the original game such as inanimate enemies in combat. Regardless, I had a blast and would recommend the game to those who enjoyed its precursors.

This review is based on a playthrough of a digital copy downloaded to the player’s Steam Deck to the standard ending with 11/29 achievements obtained.

| Score Breakdown | |

|---|---|

| The Good | The Bad |

| Engrossing battle and mapping mechanics. Good story with different branches. Great sound and sight. | Player’s party lacks backstory. Some poor narrative direction at a few points. Visuals could have been better in a few areas. |

| The Bottom Line | |

| Another excellent Etrian remaster. | |

| Platform | Steam |

| Game Mechanics | 10/10 |

| Control | 9.0/10 |

| Story | 9.0/10 |

| Localization | 9.5/10 |

| Aurals | 9.5/10 |

| Visuals | 9.0/10 |

| Lasting Appeal | 10/10 |

| Difficulty | Adjustable |

| Playtime | 12-24+ Hours |

| Overall: 9.5/10 | |

During the 8-bit and 16-bit video game console generations, North America was in a dark age when it came to Japanese roleplaying games, with many overseen for localization, as had been the case with the Final Fantasy franchise, which led to confusing renumbering of their titles that the seventh installment for the Sony PlayStation would rectify. Final Fantasy V on the Super Famicom would be one of the titles overlooked for translation until the release of the Final Fantasy Anthology for Sony’s first game console. The fifth entry would see numerous rereleases, the latest being the Final Fantasy V Pixel Remaster, which would find its way to the PlayStation 4 along with the other entries of the remake collection.

Final Fantasy V opens with a vagrant named Bartz, who, along with his trusty Chocobo named Boko, investigates a fallen meteor accompanied by an amnesiac elder named Galuf. The other deuteragonists include the princess of Tycoon, Lenna, who is searching for her father, and the pirate captain Faris, both joining Bartz to stop seals breaking to release the wicked sorcerer Exdeath. The characters are well-developed, with some decent twists, although the narrative rehashes elements from prior Final Fantasies, which include the weakening of elemental forces. The translation doesn’t detract from the lighthearted disposition, with cultural references such as the Power Rangers. However, the choices for names such as Hiryu for King Tycoon’s Wind Drake and Exdeath for the main antagonist could have been better.

The fifth installment was the second to feature the franchise’s once-signature active-time battle system, fights still randomly encountered. However, as in the PlayStation 4 and Nintendo Switch versions of the other Pixel Remasters, the player can turn random fights on or off. Boosts also return that can as much as quadruple experience, money, and job ability points, and make the game more accommodating to players of different skill levels than ever before, a godsend given that Final Fantasy V, without them, is one of the more difficult entries of the series. The structure of active-time combat remains unchanged, with the playable cast of up to four characters having speed gauges that let them perform a command when filled.

Alongside the standard system of levels from experience is the job system, returning from Final Fantasy III, albeit evolved. Upon reaching the first elemental crystal, players receive access to different vocations that affect what kind of abilities the characters can perform in combat. Among the initial classes are the Knight, which can equip swords and heavy armor and take damage instead of allies low on health; the Monk, which can deal significant damage without weapons yet can only equip lighter armor; the Thief, which can steal items from enemies; the Black Mage, which can cast offensive magic; and the White Mage, which can cast healing and defensive spells.

Jobs have levels that rise with Ability Points obtained from battle alongside standard experience and money, letting a character equip one additional command, a passive ability, or a stat increase with their current occupation’s base command. For instance, one can have a Knight that can cast White Mage spells up to a specific tier, provided the player has advanced levels in the staple Final Fantasy healing class. One major issue is that if the player continually wants to master new class skills, they can only have one extra active or passive ability while learning a particular vocation. This setup can feel constraining, but players can set their characters as Freelancers, where they can equip two job abilities.

Late in the game, the player can unlock a secret class, the Mime, that allows for far greater freedom in vocational customization and was my go-to job for all my characters during the endgame. The general restrictiveness of the job system before then is perhaps the main shortcoming of the game mechanics, and there are a few bosses that drove me to reference the internet and can be unbeatable depending upon the player’s party setup. The turbo mode players can toggle can relieve some of the grind necessary to progress without the Boosts, and some class and ability combinations can make the experience a breeze at times. Ultimately, with the adjustable challenge, the fifth entry’s Pixel Remaster is an accommodating experience.

Those who have played prior installments of the Pixel Remaster collection will be familiar with the control, with a menu system that is easy to handle and an overworld map connecting all towns and dungeons. A suspend save is also available, along with autosaving when transitioning between areas, which can be beneficial given the frequent poor placement of hard save points. The in-game maps for towns and dungeons are also helpful, although the latter can be annoying, and the direction of where to go next is frequently poor. Regardless, things could have been worse in the category of interaction.

Composer Nobuo Uematsu’s soundtrack for the fifth entry is one of his strongest, beginning with a central piece that sounds like a cross between the Indiana Jones and Back to the Future themes, along with numerous remixes of various emotions throughout the game. The Prelude and series overture are also present, and tracks such as “Clash on the Big Bridge” are equally solid, with superb instrumentation. Some silence sporadically abounds during many story scenes, but the aural experience is well above par.

Visually, the game is on par with its preceding Pixel Remasters. The original introduced effects such as various emotions for the character sprites, which retain their miniature proportions and only enlarge in combat. Some graphical laziness from the Super Famicom release returns, like the main character sprites beyond battles not showing their current jobs. Enemies in combat are also inanimate and consist of occasional reskins. However, the environments and effects within and without engagements are solid, so there is some reason to celebrate regarding the fifth remaster’s graphics.

Finally, given the possible need for grinding to make it through the main quest, total playtime ends up higher than in previous Pixel Remasters, somewhere between sixteen to twenty-four hours, with lasting appeal present as maxing every class and receiving every PlayStation Trophy. However, there are no narrative variations and above-average difficulty on default settings that may deter additional playtime.

In summation, the Pixel Remaster of Final Fantasy V is mostly on par with its predecessors, given the accommodating difficulty settings that will appeal to players of all skill levels, the quality-of-life improvements such as in-game maps, the enjoyable story and above-average translation, the superb soundtrack, and the pretty remastered visuals. However, the fifth entry leaves room for improvement even in its positive aspects, among them the restrictiveness of class development, the weak direction on advancing the central storyline, the derivative nature of some story elements, and lazy visual decisions retained from its prior ports. Regardless, while it isn’t the strongest entry of the Final Fantasy franchise, it does warrant a look from gamers exploring the storied series’ history.

This review is based on a single playthrough with all Boosts at their maximums to the standard ending and 54% of PlayStaton Trophies acquired.

| Score Breakdown | |

|---|---|

| The Good | The Bad |

| Some killer class combinations. Good story with humorous writing at times. One of Nobuo Uematsu’s best Final Fantasy soundtracks. Nice remastered visuals. Decent lasting appeal. | Class system often feels restrictive. Narrative reuses elements from past series entries. Some lazy visual direction carried over from prior versions. |

| The Bottom Line | |

| Probably the definitive version of the game. | |

| Platform | PlayStation 4 |

| Game Mechanics | 8.5/10 |

| Control | 8.5/10 |

| Story | 8.5/10 |

| Localization | 9.0/10 |

| Aurals | 9.5/10 |

| Visuals | 7.5/10 |

| Lasting Appeal | 8.0/10 |

| Difficulty | Adjustable |

| Playtime | 16-24+ Hours |

| Overall: 8.5/10 | |

When Atlus’s Etrian Odyssey for the Nintendo DS saw its North American release, most gamers found it a throwback to old-school role-playing games, given a fully customizable party, first-person dungeon exploration, and sometimes punishing difficulty. Given its success, it was natural that a sequel would see its release soon afterward, later given a 3DS remake and years later remastered for Windows and the Nintendo Switch as part of the Etrian Odyssey Origins Collection as Etrian Odyssey II HD, allowing new generations to discover the original version of the first sequel of the dungeon-crawling franchise.

Upon starting a new game, the player must create a party of five characters of diverse classes, with some new selections in the sequel, which include Gunner and War Magus. Before choosing a party, it’s a good idea to give their skill sets a once-over to ensure that whatever party the player selects can work harmoniously. For example, the Survivalist has certain skills that can grant specific allies the initiative in a round of combat, which can, for example, help healers execute their healing before the enemy kills whomever the player wishes to heal.

Battles in the labyrinth are random, with an indicator gradually turning red to indicate how close the player is to encountering enemies, a feature that, like in the first game, alleviates the typical tension associated with random encounters. Fights follow the traditional turn-based formula of inputting commands for the player’s party and letting them and the enemy beat up one another in a round, with agility determining turn order. The player puts their characters into a formation consisting of a front and back row, each able to hold up to three characters, with characters in the front row dealing and taking more damage and back row characters taking and dealing less damage.

Commands include attacking with an equipped weapon, defending, using items, attempting to escape (with up to five opportunities and an increased chance of success with a skill all characters have), changing the front and back row formation (if all characters in the front row die, the back and front rows will switch), or using a unique Force skill when a character’s Force points are at maximum. Defeating all enemies results in the player acquiring experience for all participating characters who are still alive, not to mention monster parts that the player can sell at the shop in town for money (since monsters don’t drop money themselves).

Violating the Hippocratic Oath

Sold parts gradually unlock more powerful equipment and consumable items. In some cases, gear and consumables are of limited stock, so the player must acquire more monster parts to unlock the equipment and items again for purchase. What happens when the player dies in combat depends upon the difficulty setting: the lowest challenge, Picnic, transports players back into town with no experience lost, while higher settings result in a Game Over but the chance to preserve the dungeon map.

Leveling results in the player acquiring a skill point they can invest in a character class skill tree, with upper-level skills requiring weaker skills to have a certain number of points to unlock them. Bosses end each Stratum, their difficulty depending upon the challenge mode, and as a hint for those playing on standard or advanced settings, using bind skills on their head, arms, and feet can be pivotal. Ultimately, the game mechanics are virtually flawless and accommodating to players of divergent skill levels.

The interface is mostly the same as it was in the first game, with a linear structure and a hub town where the player can perform various tasks such as buying new items and equipment, recovering health, and so forth, with expectant features like the ability to see how gear increases or decreases stats before purchasing it while shopping. The ability to map walls automatically also reduces some of the stress of dungeon cartography, and there are some improvements in dungeon navigation, primarily magnetic poles every couple of floors that provide teleportation shortcuts. Aside from the lack of visibility of stat increases or decreases when pawning equipment, control is very tight.

While one can argue that the first Etrian Odyssey sequel is light on plot, it isn’t forced down the player’s throat like in contemporary high-end video game releases. Plenty of positives include intricate backstory (especially elaborated upon towards the end), tavern quest subplots, and mysterious characters such as the adversarial dungeon-crawling duo Der Freischütz and Artelinde. The translation is equally solid, although it features some of its preceding remaster’s missteps with awkward lines such as “It’s a horde of enemies!” when targeting all monsters in battle.

An Etrian autumn

Yuzo Koshiro’s soundtrack, like in the first game, is one of its high points, with plenty of catchy, memorable tracks for each Stratum and enemy engagements, the primary battle theme changing midway through the game. Sound effects could have used more diversity at times, but otherwise, the sequel is an aural delight.

The sequel uses the same remastered visual style as its predecessor, relying on anime character portraits for the player’s characters, people in town, and occasional people in the labyrinth, with three-dimensional dungeon visuals that look nice and colorful, While the monster designs in battle look nice, they’re still inanimate, and a few reskinned foes abound. Still, the game looks good in high definition.

Finally, one can breeze through the sequel in as little as twelve hours; however, plenty of lasting appeal exists: a postgame Stratum, filling the compendia, tavern quests, and Steam achievements, which can push it well beyond that length.

In summation, Etrian Odyssey II HD is, like its predecessor, a great remaster that sports quick combat with adjustable difficulty, making it more accessible to players who would not usually enjoy such RPGs. Control and the signature cartography are also tight, the audiovisual presentation is solid, and the story has some good twists; however, many may admittedly find the narrative shallow. Regardless, the remaster of the first Etrian sequel accomplishes the goal of the remaster collection of bringing the old-school-style dungeon crawler to new audiences. Given the endless possibilities of character and party customization, it will keep prospective players occupied for a fair time.

This review is based on a playthrough to the standard ending with no postgame content attempted.

| Score Breakdown | |

|---|---|

| The Good | The Bad |

| Lots of classes and formations to mess with. Tight control. Solid audiovisual presentation. Endless lasting appeal. | Plot is thinly developed. Many areas where the graphics could have been better. |

| The Bottom Line | |

| Another great Etrian remaster. | |

| Platform | Steam |

| Game Mechanics | 10/10 |

| Control | 9.5/10 |

| Story | 9.0/10 |

| Localization | 9.5/10 |

| Aurals | 9.5/10 |

| Visuals | 9.0/10 |

| Lasting Appeal | 10/10 |

| Difficulty | Adjustable |

| Playtime | 12-24+ Hours |

| Overall: 9.5/10 | |

Let me begin this deep look by saying I do not like Nintendo’s Legend of Zelda series, and consider it one of the most overrated franchises in gaming history. There are a few entries that I enjoyed, such as the Triforce of the Gods games (A Link to the Past and A Link Between Worlds), but I believe that the franchise especially went downhill when it leaped from two to three dimensions. Even then, I didn’t care much for Ocarina of Timeor its rerelease on the Nintendo 3DS. I remember buying a Nintendo Switch because of Breath of the Wild’s “universally positive” reception, but I still didn’t like it. The Legend of Zelda: Tears of the Kingdom continues the open-world direction the franchise has headed in, and while I really wanted to like the game, it just didn’t love me back.

Tears of the Kingdom occurs several years after Breath of the Wild, with Link and Zelda exploring the caves below Hyrule Castle, from which toxic Gloom has been sickening citizens of the kingdom. After encountering a mysterious mummy, an event known as the Upheaval occurs that results in Link losing the power that he had acquired in the game’s predecessor, with floating islands and poisonous Depths appearing as well. Some of the backstory is good, but the narrative doesn’t really strike any new ground, and in general, once you’ve experienced one Zelda game’s plot, you’ve pretty much experienced them all. The translation is legible, but Nintendo of America, as in recent years, didn’t really put much effort into making it sound realistic and fitting for a fantasy game, also annoyingly using the acronym OK instead of “okay” among other things.

And makes the endgame nigh unplayable.

Many elements from Breath of the Wild return, such as Link being able to find different kinds of melee/ranged weapons and shields that break after excessive use, with an initial limit as to how many he can carry at a time, but players late into the game can use Korok Seeds strewn throughout Hyrule to increase these limitations, which I only found out about via the internet. Shrines return, where Link, in most cases, must solve a complex puzzle to receive a Light of Blessing, four of which he can use to extend his life or stamina meters at Goddess Statues. Link can also obtain additional Hearts at points, including finishing one of the main Temples necessary to advance the storyline.

Players can outfit Link with clothing for his head, body, and legs for defensive power and increase it at Great Fairy Fountains throughout Hyrule; however, gaining access to their power is difficult without a guide. Certain clothes are necessary to traverse areas with extreme heat or cold without suffering damage, sometimes available in the regions where such conditions occur. Combat largely remains the same as in prior three-dimensional Zeldas, with Link able to lock on to an enemy within his view, attack it, block its attacks with his shield, and execute moves such as side jumps and backflips.

Lamentably, the same problems in combat carry over from prior 3-D Zelda installments, where switching a target necessitates that the player release the targeting button, get close to another enemy, and hold the same button. Moreover, the minimap doesn’t show enemy locations on the battlefield, which leaves Link completely blind from behind. Furthermore, if his back is near a wall, the camera can go haywire, and Link can leap and grab said wall, making him vulnerable to the enemy. Most of the time, killing enemies nets Link parts and armaments he can seize for himself.

Throughout his lengthy journey, Link gains several powers instrumental in solving the myriad puzzles present in most series predecessors. First is Ultrahand, which allows Link to telekinetically move an object around and rotate it in any direction except port or starboard, which leads to many annoying moments. Players can attach movable objects to one another and break one piece from another by wiggling the right stick. This ability plays significantly into advancing through the Temples Link accesses and completing Shrines scattered throughout Hyrule. However, I found it incredibly difficult to discover many Shrines and solve their respective puzzles, if present, without the internet.

Link’s a lumberjack, he’s…not okay.

Another ability Link acquires includes Fuse, which can allow him to fuse one of his breakable melee weapons and shields with a specific material gotten from defeating monsters or battlefield objects such as wooden crates or boulders, which renders it unchangeable until it breaks. He can also attach materials to arrows he can shoot from one of the bows he can carry to provide effects such as homing guidance towards enemies, which can fare well against those with unpredictable movement patterns. Sometimes, Link can pick the arrows he fires back up if they fail to strike a monster, provided the player can track them down.

Link also gains the Recall ability, which can target a single object and reverse its movement, be it one he has moved through Ultrahand or a moving part of an environment such as a giant cog, often necessary to solve some Shrine puzzles. Furthermore, players can photograph monsters and most weapons, shields, bows, and items they drop to note them in the various compendia, a tedious task when other roleplaying games automatically do so. The Ascend ability allows him to leap through a ceiling if it isn’t too high above and emerge at the top.

While Tears of the Kingdom has its fun moments, given the various killer moves Link can execute, there exist many issues aside from those mentioned that prevent it from being wholly enjoyable, especially toward the end when he must traverse the Depths for the endgame sequence and risk losing maximum life due to Gloom that infests the underworld which seems to exist solely to artificially make the game longer than it needs to be, with the potential to go into the final battles with a low number of Hearts. While there are food recipes that can cure Gloom taint, players will need to go through hoops to get the ingredients to make them, which again can necessitate the internet, which is the only possible way to get through the game in a reasonable time.

Moving to control, while players can theoretically record their progress anywhere, they cannot simply quit in the middle of a drawn-out puzzle and expect progress to remain, with the frequent load times, inexcusable in a cartridge game, not helping, and the autosave feature can be unreliable. Another major problem is the absence of automapping, which would have made discovering the Shrines and other locales of Hyrule easier, with segments of the country mapped entirely alongside no indicator of where the player has been when Link visits one of the Skyview Towers. Even then, Link sometimes must go through hoops to activate them in the first place. The teleportation between Shrines is a godsend, but Tears of the Kingdom could have been more user-friendly.

Vending machines were all the rage in ancient Hyrule.

Like Breath of the Wild, the sequel has a minimalistic musical presentation. While there are some decent tracks, the aurals rely too much upon ambiance. The sound effects are good, but the quality of the voicework is mixed, with some annoying performances and lots of annoying grunting during cutscenes not fully voiced. Thus, one could get away with muting the volume and listening to other music while playing the game.

The visuals are mostly the same as in Breath of the Wild, with a cel-shaded style that superficially appears decent, and the lighting effects and colors are genuinely beautiful. However, there are many technical hiccups, including a choppy framerate, environmental pop-up, blurry and pixilated texturing, and jaggies. Moreover, Link eating phantom food whenever the player uses food items in the game menus looks asinine. Ultimately, the game is only graphically acceptable.

When ceasing to play the Breath of the Wild sequel, my playtime numbered around seventy-two hours, with plenty of Shrines yet to discover and many sidequests left incomplete. While the supplemental content would theoretically enhance the lasting appeal, only those who somehow enjoy the game would want to play onward.

Overall, Tears of the Kingdom, like Breath of the Wild before it, was for me a massive letdown, given its tedious gameplay and control, hackneyed writing, and average audiovisual presentation, with the Zelda series and open worlds, in my opinion, going together as well as a fish and a bicycle. However, if you liked the first Nintendo Switch Zelda, you would probably enjoy its sequel, but there are far better open-world RPGs. Those in search of the definitive Zelda experience would be far better off playing one of the genuine classics of the franchise like A Link to the Past and A Link Between Worlds. Regardless, if I could use Link’s Recall ability on the time I spent with the game, I would do so in a heartbeat.

This deep look is based on an incomplete playthrough of around seventy-two hours to the “Destroy Ganondorf” quest.