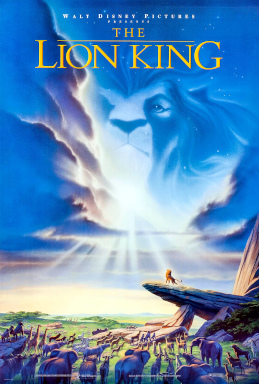

Film Review – The Lion King (1994)

Simba the Brownish Gold Lion

When I was young and carefree, I didn’t really have strong opinions on anything like most media, video games included (and I’ve been a gamer for as long as I remember), or any other media like books, movies, and television shows. In the early 1990s, I did have a slight interest in Disney’s animated films and had seen many in the theaters then, but when The Lion King came out in 1994, refused the opportunity to see it with my family when we visited my late maternal grandparents then. Since then, I hadn’t actually seen the film in its entirety to the point I could remember it, but recently watched it in full on Disney+ to celebrate its thirtieth anniversary.

The film opens with the iconic “Circle of Life” musical number and sequence where the newborn Simba, son of King Mufasa, is presented to the animal population of the Pride Lands. When Simba grows up, his father teaches him about royal responsibilities and preserving the “circle of life,” which connects all living entities. However, Mufasa hypocritically excludes the hyenas from it, with his effeminate younger brother, Scar, conspiring with them to seize the throne for himself. Some of the character names, Scar’s included, create an Aerith and Bob situation, like the main hyenas being named Shenzi, Banzai, and…Ed. Scar’s birth name, Taka, is never mentioned within the film, and a flashback in the future series The Lion Guard shows how he got his namesake facial blemish.

“When we die, our bodies become the grass, and the antelope eat the grass. And so we are all connected in the great Circle of Life…but not the hyenas.”

Young Simba is a bit of a brat, and many musical numbers feel a bit excruciating, such as “I Just Can’t Wait to Be King” (which steals a bit from Dolly Parton’s “9 to 5”), and “Be Prepared” (sharing its name with the Boy Scout motto doesn’t help). Scar ultimately tricks his nephew into going into the middle of a gorge while having the hyenas incite a stampede of wildebeests try to kill him, which results in Mufasa rescuing him but being killed himself in the process. Simba is blamed (mostly rightfully) for killing the king, with his uncle telling him to run away, which he does.

Simba eventually encounters the vagrant meerkat Timon and the warthog Pumbaa, who teach him through song “hakuna matata,” the art of not giving a damn, which he masters into adulthood. He rescues the two from his old friend Nala, with whom he falls in love, and who tells him that the Pride Lands has become drought-stricken under Scar’s reign. The film shows no logical explanation as to exactly how they did, with starvation present as well due to the lionesses refusing to hunt, so one could count them among the real villains of the movie alongside Mufasa.

The real heroes of the film.

After a celestial visit from his father, Simba returns to the Pride Lands to confront his uncle, with the rest of the film having plenty of callbacks to the first act. Overall, The Lion King definitely has many positive aspects, including the soundtrack (with exceptions such as a few of the musical numbers), strong voice performances (including James Earl Jones as Mufasa, Jeremy Irons as Scar, and Whoopi Goldberg and Cheech Marin as the hyenas Shenzi and Banzai), and parallels to William Shakespeare’s Hamlet. However, the movie does derive elements from Osamu Tezuka’s Kimba the White Lion, and there are others issues like zero in-film explanation about the climate during Scar’s kingship. Regardless, it’s easily a bucket-list animated film, but as with many others, that’s far from synonymous with “masterpiece.”

| The Good | The Bad |

|---|---|

| Hamlet, but with lions. Great voice performances. Beautiful animation. Nice ethnic soundtrack. | Some unexplained plot elements. Borrows elements from Kimba the White Lion. A few excruciating musical numbers. Toilet humor. |

| The Bottom Line | |

| A must-see Disney classic, but not synonymous with “masterpiece.” | |

| |